Volume 10, Issue 2 (5-2023)

JROS 2023, 10(2): 101-108 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Momen O, Gorgani Firouzjah H, Sahebjamei A, Paryab M, Arab M, Ghandhari H. Predictors of Neurological Recovery in Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury Patients: A Multicenter Cohort Study. JROS 2023; 10 (2) :101-108

URL: http://jros.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2258-en.html

URL: http://jros.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2258-en.html

Omid Momen1

, Habib Gorgani Firouzjah1

, Habib Gorgani Firouzjah1

, Afshin Sahebjamei1

, Afshin Sahebjamei1

, Mansoor Paryab2

, Mansoor Paryab2

, Mahsa Arab2

, Mahsa Arab2

, Hasan Ghandhari3

, Hasan Ghandhari3

, Habib Gorgani Firouzjah1

, Habib Gorgani Firouzjah1

, Afshin Sahebjamei1

, Afshin Sahebjamei1

, Mansoor Paryab2

, Mansoor Paryab2

, Mahsa Arab2

, Mahsa Arab2

, Hasan Ghandhari3

, Hasan Ghandhari3

1- Department of Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran.

2- 5th Azar Hospital, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran.

3- Department of Orthopedics, Bone and Joint Reconstruction Research Center, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- 5th Azar Hospital, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran.

3- Department of Orthopedics, Bone and Joint Reconstruction Research Center, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 534 kb]

(134 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (934 Views)

Full-Text: (187 Views)

Introduction

Traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI) is a well-known health challenge worldwide that has increased significantly in recent years [1, 2]. In addition to the mortality caused by TSCI, which is reported above in severe cases, the complications and outcomes of TSCI, including functional and neurological disabilities due to the need for expensive and complex medical support in TSCI patients, impose a significant burden on economic and health systems [1, 3, 4]. The prevalence of TSCI varies across geographical regions [3, 5, 6, 7]. According to the latest reports, the incidence and prevalence of TSCI at the global level are 0.9 (a range of 0.7 to 1.2 million) and 20.6 (a range of 18.9 to 23.6 million cases), respectively [5]. Traffic injuries, falls, work-related injuries, violent crimes, and sports-related injuries are the known causes of TSCI. Its prevalence is more common in men than in women and in the age range of 20 to 30 years than other ages [7, 8, 9].

Neurological injuries are among the most severe and common outcomes of TSCI [10]. Most patients’ neurological recovery after a spinal cord injury (SCI) occurs in the first six months following the accident, but progress can be monitored for up to five years [11]. The prognosis for nerve recovery varies and is mainly determined by the initial severity of the nerve damage. A higher degree of early injury suggests a worse one-year prognosis [12, 13].

Neurological examinations with the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (ISNCSCI) endorsed by the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) and the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCOS) is the safest way to diagnose and classify the level and degree of TSCI [14]. However, the use of imaging techniques, both as a support method for diagnosis and to identify possible accompanying injuries, is undeniable, and direct evaluation of the spinal cord parenchyma is only possible using imaging techniques [14].

TSCI may lead to physical, social, and occupational disorders in people [9]. Permanent loss of sensation and motor ability is common in patients with severe TSCI [6]. Clinical outcomes and neurological recovery after TSCI depend on various factors [11, 15, 16]. Therefore, considering the importance of this topic, this study was conducted to investigate the clinical outcomes and predictive factors of patients with TSCI.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, the medical records of 154 patients with TSCI referred to the emergency department of an educational center (5 Azar Hospital) affiliated with Golestan University of Medical Sciences between 2014 and 2021 were reviewed. Convenience sampling was performed for all referring patients in this time interval. The definitive diagnosis of TSCI was made by a spine specialist based on neurological examinations and radiographic results (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]). Finally, the medical profiles of the 120 patients were evaluated.

The inclusion criteria included a definite diagnosis of SCA, follow-up for at least 12 months after the operation, and access to clinical and radiographic findings of the patients. The exclusion criteria included other neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), and other skeletal-neurological diseases that can lead to neurological disorders in patients, patients with TSCI with an unknown mechanism, and lack of access to clinical outcomes.

Patient data were collected using a two-part checklist, including demographic characteristics (age, sex, and body mass index [BMI]) and clinical findings (disease severity, time of hospitalization, initial evaluations upon entering the emergency room, duration of surgery, type of spine surgery, medicines used, duration of hospitalization and functional and neurological outcomes).

TSCI severity was assessed using the ASIA impairment scale [17]. The classification was as follows: Complete defect (grade A); sensory function, but not motor function, was preserved below the nerve level, and some sensation was preserved in the S4 and S5 sacral segments (grade B); motor function was preserved below the nerve level, but more than half of the key muscles below the nerve level had muscle grade <3 (grade C), motor function was preserved below the nerve level, and at least half of the key muscles below the nerve level had muscle grade three or more (grade D) and typical performance (grade E).

Two independent researchers (neurologists and spine surgeons) classified TSCI. Their agreement was evaluated using the Cronbach α. The Cronbach α coefficient for TSCI severity classification was 0.91 (in the range of 0.88 to 0.95), which is excellent.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 22. Descriptive statistics were used to report qualitative variables. Quantitative variables were reported as Mean±SD. Using the Smirnov test, Kolmogorov evaluated the normality of the distribution of quantitative variables. To compare quantitative variables between groups (TSCI severity), assuming a normal distribution of variables, a t-test was used, and if normality was not established, the Mann-Whitney test was used. To compare the variables in more than two groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the assumption of normality and Kruskal-Wallis test with the assumption of non-normality was used. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine the relationship between qualitative variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis with a backward method investigated vital factors predicting outcomes in patients with TSCI. The effect size was reported as odds ratios (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (95 % CI). P<0.05 was considered as a statistical significance level.

Results

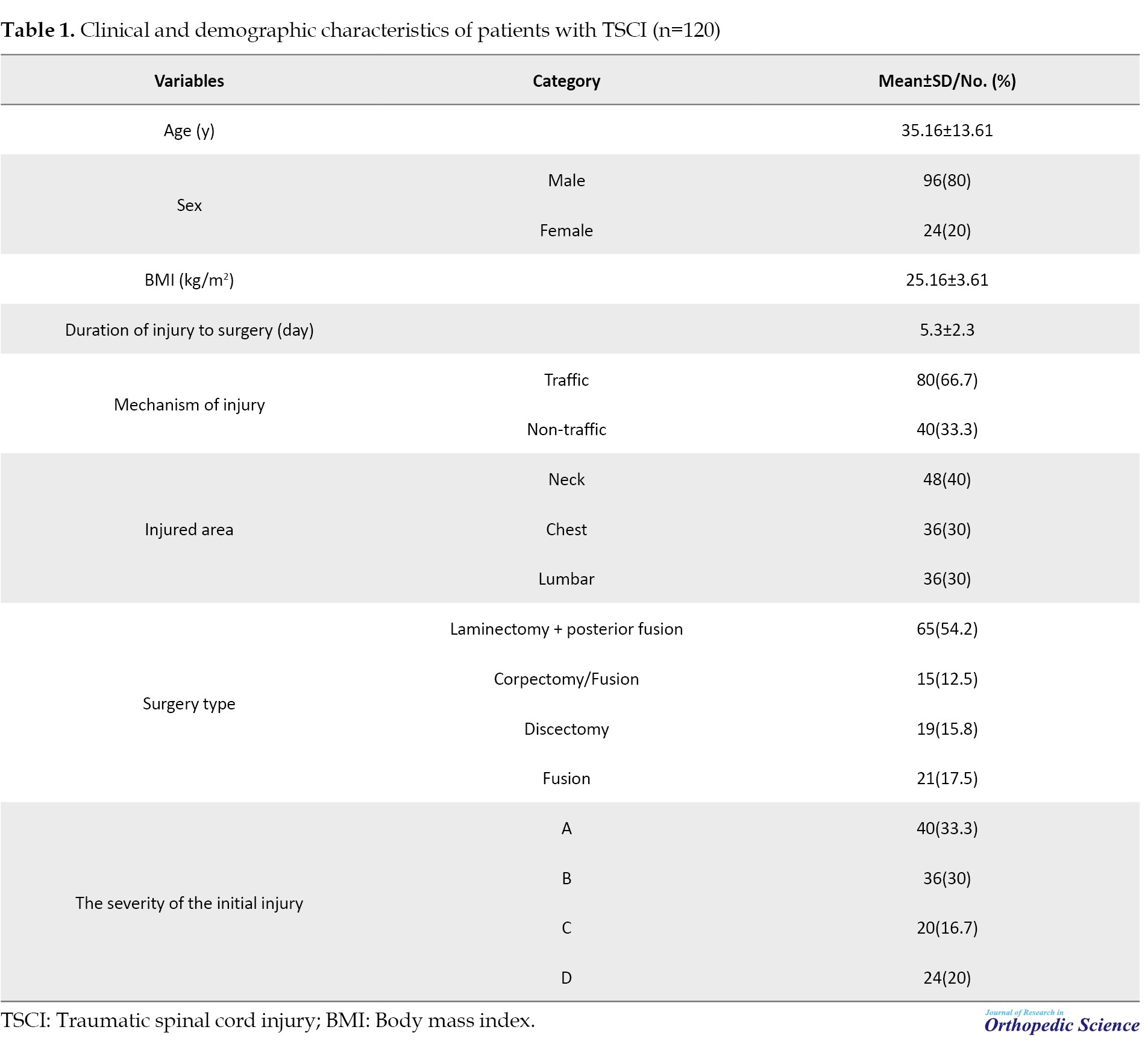

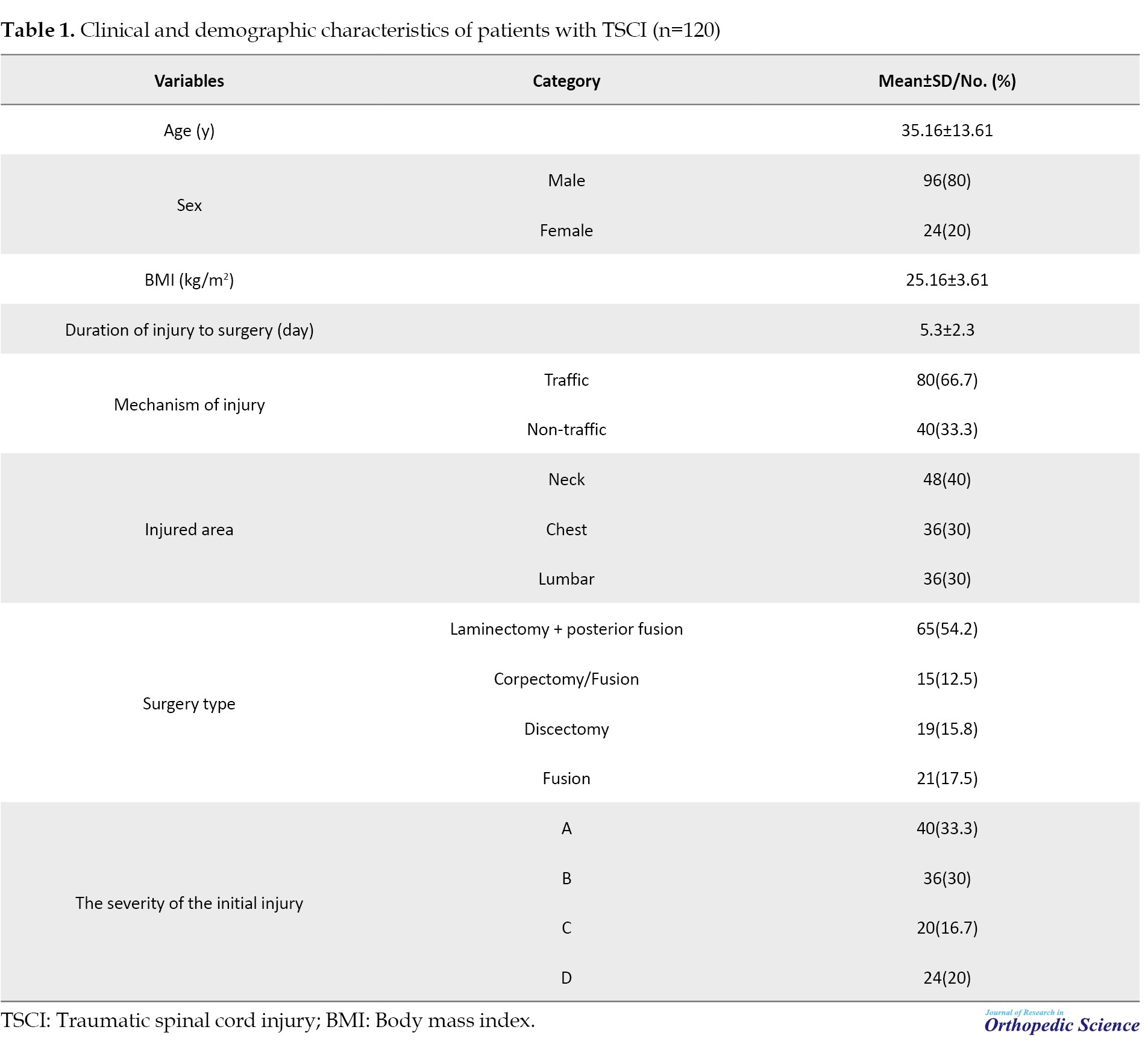

The mean age of patients was 35.16±13.61 years (range: 18 to 45 years). Ninety-six patients (80%) were men. The mean BMI) was 25.16±3.61 kg/m2. The mean duration of the injury to the operation of TSCI patients was 5.3±2.3 days. Twenty-four patients (80%) had a history of corticosteroid use. Traffic accidents were the most common cause of trauma in 80 patients (66.70%). In terms of injury area, 48 patients (40%) had neck injuries, 36(30%) had chest injuries, and 36(30%) had back injuries. The most commonly performed surgery was laminectomy + posterior fusion, which was performed in 46.70% of the patients (Table 1).

In terms of initial neurological status, 40 patients (33.30%) had ASIA impairment scale (AIS)-A, 36(30%) had AIS-B, 20(16.70%) had AIS-C, and 24(20%) had AIS-D. None of the patients had an AIS-E initial neurological status.

Neurological outcomes after surgical treatment

One year after treatment, no improvement was observed in 32 patients (26.70%). Although 88 patients (73.3%) had some degree of sensory or motor limitation, the condition of these patients was significantly improved compared to before surgery. The mean of hospitalization was 13.7±23.47. In addition, 91 patients (75.8%) had no postoperative complications. However, 15 patients (12.5%) had bedsores, three patients (2.5%) had respiratory problems, and 11 patients (9.2%) had other complications. Eight patients (6.70%) died.

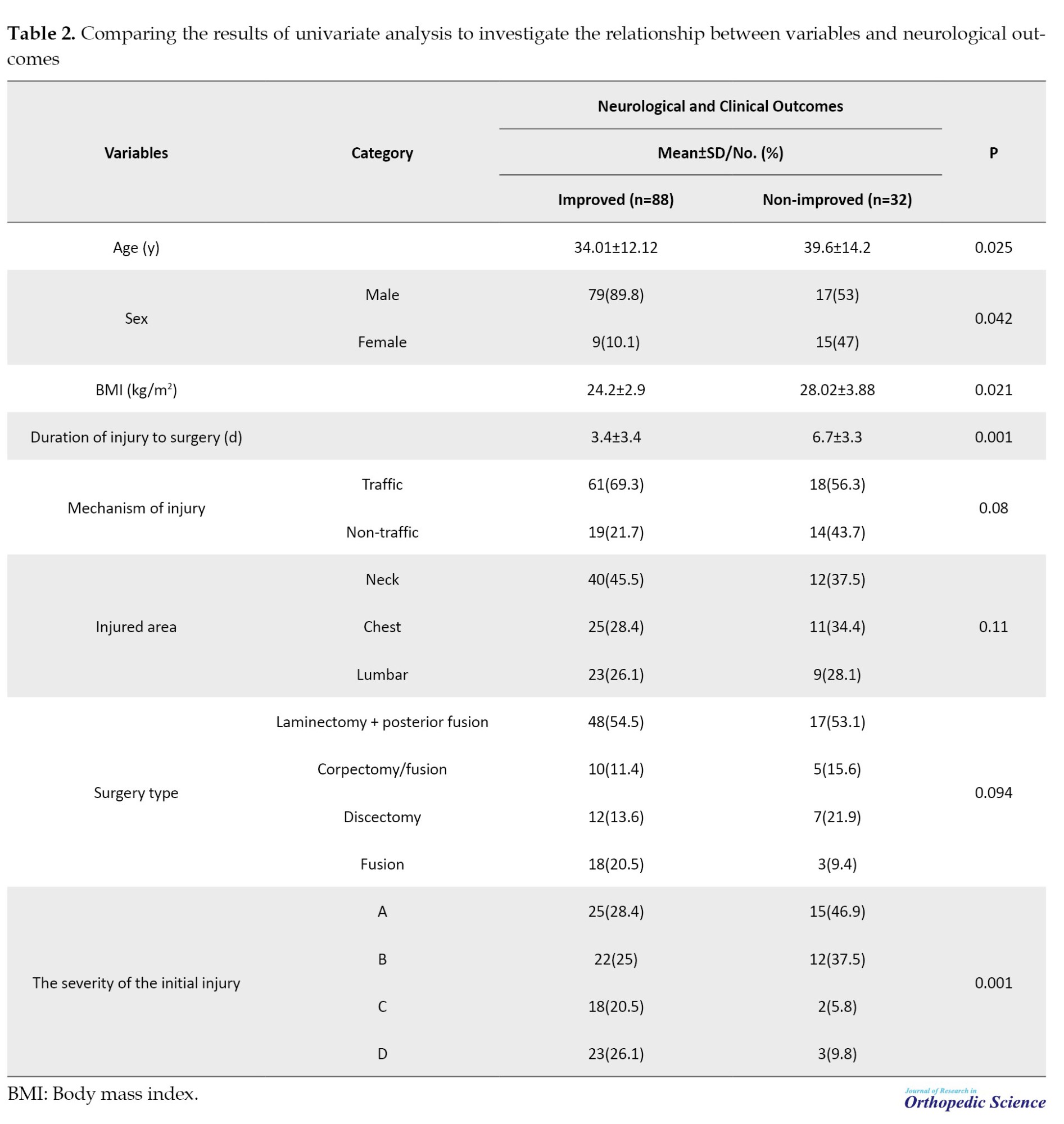

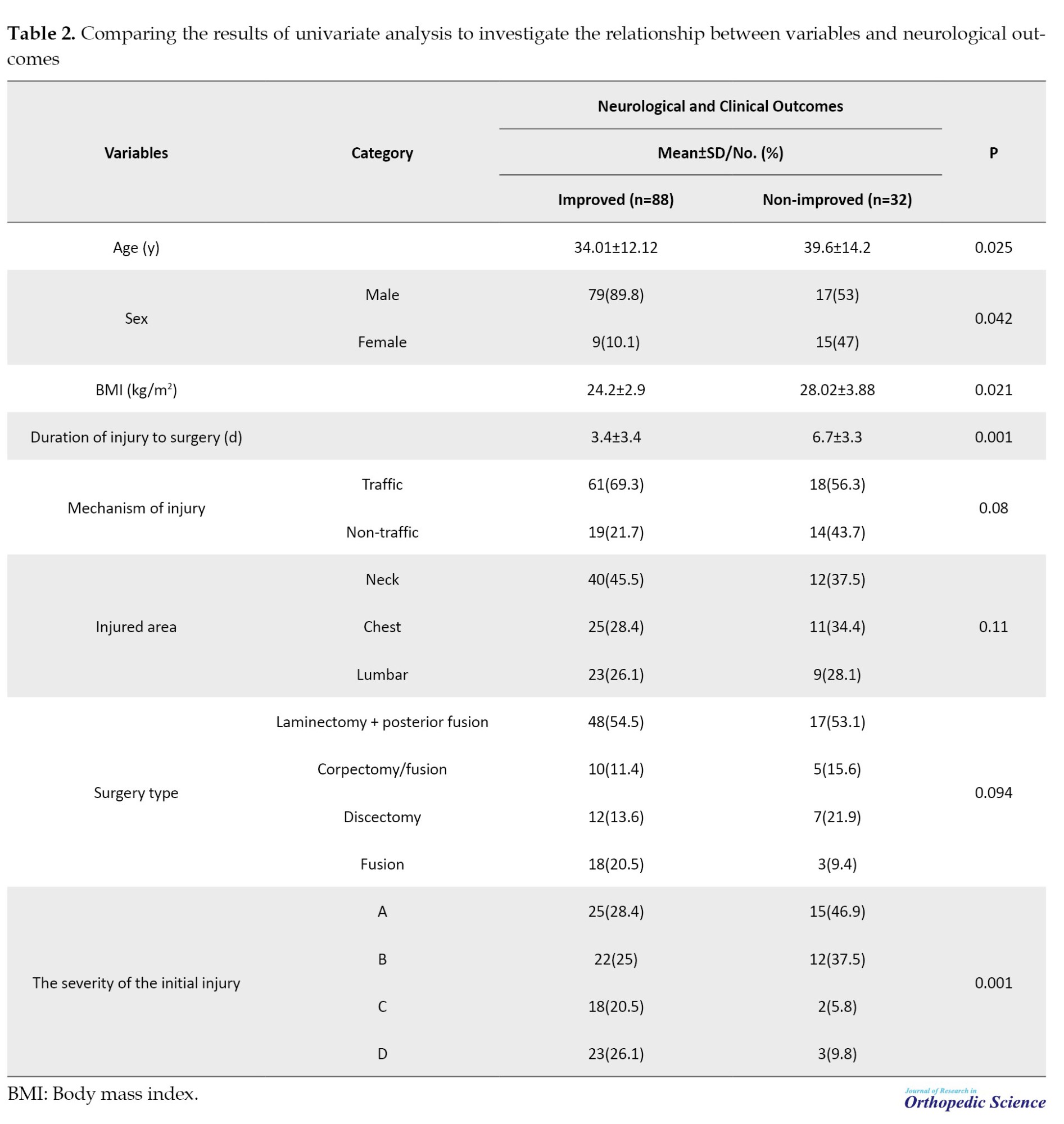

The mean age of patients with recovery was significantly lower than non-recovery patients (34.01±12.12 vs 39.6±14.2 years, P=0.025). The proportion of men in the group with improvement was significantly higher than that in the group without improvement (89.8% vs 53%). The severity of the initial injury was significantly related to the recovery rate, and patients with injury levels C or D had significantly more recovery. Also, the mean BMI was lower in patients with improvement than those without improvement (P=0.021). The mean duration from injury to surgery was significantly shorter in patients with recovery than those without recovery (3.4±3.4 vs 6.7±3.3). No significant correlation was observed between neurological recovery rate and other variables (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis

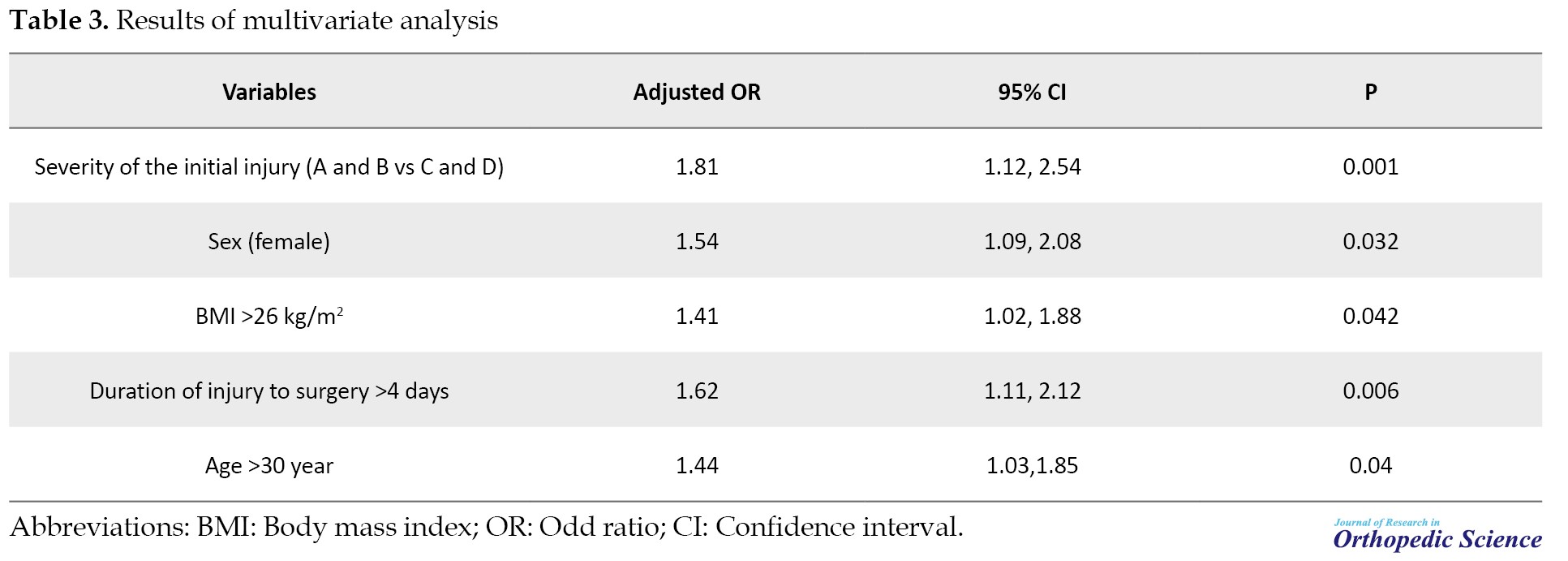

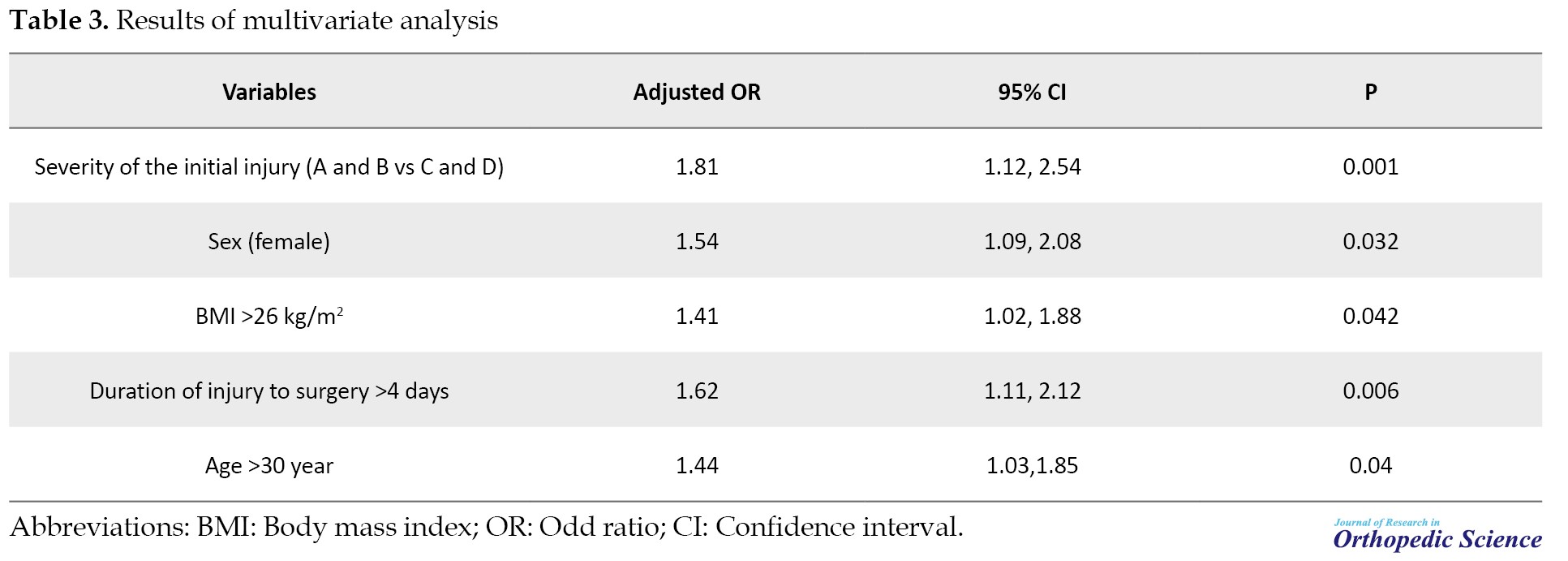

The results of multivariate analysis showed that age >30 years, female gender, BMI >26 kg/m2, duration of injury to surgery >4 days, and the severity of the initial injury (A and B vs C and D) were significantly related to increased risk of on-recovery of neurological outcomes (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study showed that the frequency of TSCI was higher in men in their second and third decades of life. The average duration from injury to surgery depends on the injury’s severity; more than half of the patients underwent surgery more than five years after injury. Twelve months after the surgery, no neurological improvement was observed in nearly one-fourth of patients. Nearly 75% of patients had improved neurological outcomes compared to those before surgery, and neurological function had reached a normal level in nearly 20% of patients. The improvement in neurological outcomes was significantly better in men than in women and in those ages <30 years than in those aged 30 years. In addition, the amount of biodegradation in obese or overweight people was significantly higher than that in people with a higher BMI. Surgery in the first few days after injury (<4 days) can be associated with improved neurological outcomes. The recovery rate of neurological outcomes was significantly lower in patients with more severe forms of injury based on the AIS classification, consistent with the results of studies conducted in this field [18-20].

In a 2022 study, Mora-Boga et al. [19] evaluated the predictors of neurological recovery in 296 patients with TSCI and showed that the rate of improvement in neurological outcomes was significantly related to the severity of the initial injury. The recovery rate was significantly higher in patients with a less severe injury. In our study, the chance of recovery was significantly higher in patients with early forms of the disease than in those with more severe forms.

Consistent with the results of our study, Wichmann et al. [21] evaluated 143 patients with TSCI and showed that the chances of recovery of functional and neurological outcomes were significantly related to the severity of the initial injury based on the AIS and the duration of the injury to surgery. They also showed that ASIA motor score (AMS) was associated with improved neurological outcomes while having prior underlying diseases reduced the chance of improved neurologic and functional outcomes. We could not estimate AMS in our study. Moreover, considering that most of our patients were <40 years old, the prevalence of underlying diseases in those patients is very low, and due to the small sample size in the subgroup of underlying diseases, we could not estimate its effect. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Ma et al. [22] reported that serial treatment of patients with TSCI with immediate decompression in the first hours after the injury (first 8 hours) can be significantly associated with neurological improvement. Evaniew et al. [16] evaluated 85 patients with TSCI and showed that older age, female sex, and delay in treatment were significantly associated with decreased neurological recovery, which is consistent with our results. Kao et al. [23] showed that obesity was negatively correlated with motor functional independence measure (mFIM) improvement. They showed that neurological improvement was lower in patients with a higher BMI than in those with a BMI, which was consistent with the results of our study.

The difference in rehabilitation recovery can be explained by the difference in characteristics and treatment participation between patients with inappropriate weight and those with normal weight. Tian et al. [24] showedthat participation in rehabilitation treatments was lower in patients with high body weight (BMI) than in patients with normal weight.

Facchinello et al. [20] showed that injury severity score, age, nerve level, and preoperative delay were predictors of neurological outcomes, which confirmed the results of our study. Contrary to our results, Furlan et al. [25] did not report a significant relationship between age and neurological recovery. This difference can be explained by the differences in the sample size and characteristics of the patients examined in the two studies.

Consistent with the results of our study, Heller et al. [18] showed that treating patients with TSCI in the first hours and days after injury was significantly associated with improved functional and neurological outcomes. They also showed that the improvement in the results was significantly related to the age of the patients, and the improvement was significantly higher in younger patients. This mechanism may be due to the increased inflammation in the early stages of ASI. They reported that an increase in the intermediate CD14-/CD16+/IL10+/CXCR4int monocyte subpopulation significantly enhanced the immune response in the early hours and days after injury. They reported that increased initial concentrations of CD14-/CD16+/IL10+/CXCR4int monocytes were associated with a higher probability of CNS regeneration and improved neurological recovery.

Conclusion

Our study showed that neurological recovery was higher in men than in women. Neurological recovery was lower in patients older than 30 years with a non-normal body mass profile (overweight or obese). Treatment in the early days and hours was associated with improved neurological recovery, while the severity of the initial injury was significantly associated with decreased neurological recovery.

Limitations

Our study had strengths and weaknesses. The most crucial weakness of this study was the short follow-up period of the patients and the small sample size of the subgroup with no recovery. We assessed neurologic outcomes 12 months after treatment, and the results may differ in longer-term follow-ups with larger sample sizes. In addition, due to the study design, we could not estimate a number of essential indicators, such as AMS, which may affect the study’s results. The design of prospective studies with a more extended follow-up period and a larger sample size can help make a more accurate estimate. The vital strength of this study was that it investigated the predictors of neurological recovery in a suitable sample size of TSCI patients in a multi-centered manner in the Iranian population.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran (Code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1401.505).

Funding

This study was taken from the orthopaedic surgery residency thesis of Mansour Paryab, approved by the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Hasan Ghandhari and Omid Momen; Methodology: Omid Momen; Investigation and data collection: Mansour Paryab; Data analysis: Mansour Paryab and Mahsa Arab; Writing: Habib Gorgani Firouzjah, and Afshin Sahebjamei.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI) is a well-known health challenge worldwide that has increased significantly in recent years [1, 2]. In addition to the mortality caused by TSCI, which is reported above in severe cases, the complications and outcomes of TSCI, including functional and neurological disabilities due to the need for expensive and complex medical support in TSCI patients, impose a significant burden on economic and health systems [1, 3, 4]. The prevalence of TSCI varies across geographical regions [3, 5, 6, 7]. According to the latest reports, the incidence and prevalence of TSCI at the global level are 0.9 (a range of 0.7 to 1.2 million) and 20.6 (a range of 18.9 to 23.6 million cases), respectively [5]. Traffic injuries, falls, work-related injuries, violent crimes, and sports-related injuries are the known causes of TSCI. Its prevalence is more common in men than in women and in the age range of 20 to 30 years than other ages [7, 8, 9].

Neurological injuries are among the most severe and common outcomes of TSCI [10]. Most patients’ neurological recovery after a spinal cord injury (SCI) occurs in the first six months following the accident, but progress can be monitored for up to five years [11]. The prognosis for nerve recovery varies and is mainly determined by the initial severity of the nerve damage. A higher degree of early injury suggests a worse one-year prognosis [12, 13].

Neurological examinations with the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (ISNCSCI) endorsed by the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) and the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCOS) is the safest way to diagnose and classify the level and degree of TSCI [14]. However, the use of imaging techniques, both as a support method for diagnosis and to identify possible accompanying injuries, is undeniable, and direct evaluation of the spinal cord parenchyma is only possible using imaging techniques [14].

TSCI may lead to physical, social, and occupational disorders in people [9]. Permanent loss of sensation and motor ability is common in patients with severe TSCI [6]. Clinical outcomes and neurological recovery after TSCI depend on various factors [11, 15, 16]. Therefore, considering the importance of this topic, this study was conducted to investigate the clinical outcomes and predictive factors of patients with TSCI.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, the medical records of 154 patients with TSCI referred to the emergency department of an educational center (5 Azar Hospital) affiliated with Golestan University of Medical Sciences between 2014 and 2021 were reviewed. Convenience sampling was performed for all referring patients in this time interval. The definitive diagnosis of TSCI was made by a spine specialist based on neurological examinations and radiographic results (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]). Finally, the medical profiles of the 120 patients were evaluated.

The inclusion criteria included a definite diagnosis of SCA, follow-up for at least 12 months after the operation, and access to clinical and radiographic findings of the patients. The exclusion criteria included other neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), and other skeletal-neurological diseases that can lead to neurological disorders in patients, patients with TSCI with an unknown mechanism, and lack of access to clinical outcomes.

Patient data were collected using a two-part checklist, including demographic characteristics (age, sex, and body mass index [BMI]) and clinical findings (disease severity, time of hospitalization, initial evaluations upon entering the emergency room, duration of surgery, type of spine surgery, medicines used, duration of hospitalization and functional and neurological outcomes).

TSCI severity was assessed using the ASIA impairment scale [17]. The classification was as follows: Complete defect (grade A); sensory function, but not motor function, was preserved below the nerve level, and some sensation was preserved in the S4 and S5 sacral segments (grade B); motor function was preserved below the nerve level, but more than half of the key muscles below the nerve level had muscle grade <3 (grade C), motor function was preserved below the nerve level, and at least half of the key muscles below the nerve level had muscle grade three or more (grade D) and typical performance (grade E).

Two independent researchers (neurologists and spine surgeons) classified TSCI. Their agreement was evaluated using the Cronbach α. The Cronbach α coefficient for TSCI severity classification was 0.91 (in the range of 0.88 to 0.95), which is excellent.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 22. Descriptive statistics were used to report qualitative variables. Quantitative variables were reported as Mean±SD. Using the Smirnov test, Kolmogorov evaluated the normality of the distribution of quantitative variables. To compare quantitative variables between groups (TSCI severity), assuming a normal distribution of variables, a t-test was used, and if normality was not established, the Mann-Whitney test was used. To compare the variables in more than two groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the assumption of normality and Kruskal-Wallis test with the assumption of non-normality was used. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine the relationship between qualitative variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis with a backward method investigated vital factors predicting outcomes in patients with TSCI. The effect size was reported as odds ratios (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (95 % CI). P<0.05 was considered as a statistical significance level.

Results

The mean age of patients was 35.16±13.61 years (range: 18 to 45 years). Ninety-six patients (80%) were men. The mean BMI) was 25.16±3.61 kg/m2. The mean duration of the injury to the operation of TSCI patients was 5.3±2.3 days. Twenty-four patients (80%) had a history of corticosteroid use. Traffic accidents were the most common cause of trauma in 80 patients (66.70%). In terms of injury area, 48 patients (40%) had neck injuries, 36(30%) had chest injuries, and 36(30%) had back injuries. The most commonly performed surgery was laminectomy + posterior fusion, which was performed in 46.70% of the patients (Table 1).

In terms of initial neurological status, 40 patients (33.30%) had ASIA impairment scale (AIS)-A, 36(30%) had AIS-B, 20(16.70%) had AIS-C, and 24(20%) had AIS-D. None of the patients had an AIS-E initial neurological status.

Neurological outcomes after surgical treatment

One year after treatment, no improvement was observed in 32 patients (26.70%). Although 88 patients (73.3%) had some degree of sensory or motor limitation, the condition of these patients was significantly improved compared to before surgery. The mean of hospitalization was 13.7±23.47. In addition, 91 patients (75.8%) had no postoperative complications. However, 15 patients (12.5%) had bedsores, three patients (2.5%) had respiratory problems, and 11 patients (9.2%) had other complications. Eight patients (6.70%) died.

The mean age of patients with recovery was significantly lower than non-recovery patients (34.01±12.12 vs 39.6±14.2 years, P=0.025). The proportion of men in the group with improvement was significantly higher than that in the group without improvement (89.8% vs 53%). The severity of the initial injury was significantly related to the recovery rate, and patients with injury levels C or D had significantly more recovery. Also, the mean BMI was lower in patients with improvement than those without improvement (P=0.021). The mean duration from injury to surgery was significantly shorter in patients with recovery than those without recovery (3.4±3.4 vs 6.7±3.3). No significant correlation was observed between neurological recovery rate and other variables (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis

The results of multivariate analysis showed that age >30 years, female gender, BMI >26 kg/m2, duration of injury to surgery >4 days, and the severity of the initial injury (A and B vs C and D) were significantly related to increased risk of on-recovery of neurological outcomes (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study showed that the frequency of TSCI was higher in men in their second and third decades of life. The average duration from injury to surgery depends on the injury’s severity; more than half of the patients underwent surgery more than five years after injury. Twelve months after the surgery, no neurological improvement was observed in nearly one-fourth of patients. Nearly 75% of patients had improved neurological outcomes compared to those before surgery, and neurological function had reached a normal level in nearly 20% of patients. The improvement in neurological outcomes was significantly better in men than in women and in those ages <30 years than in those aged 30 years. In addition, the amount of biodegradation in obese or overweight people was significantly higher than that in people with a higher BMI. Surgery in the first few days after injury (<4 days) can be associated with improved neurological outcomes. The recovery rate of neurological outcomes was significantly lower in patients with more severe forms of injury based on the AIS classification, consistent with the results of studies conducted in this field [18-20].

In a 2022 study, Mora-Boga et al. [19] evaluated the predictors of neurological recovery in 296 patients with TSCI and showed that the rate of improvement in neurological outcomes was significantly related to the severity of the initial injury. The recovery rate was significantly higher in patients with a less severe injury. In our study, the chance of recovery was significantly higher in patients with early forms of the disease than in those with more severe forms.

Consistent with the results of our study, Wichmann et al. [21] evaluated 143 patients with TSCI and showed that the chances of recovery of functional and neurological outcomes were significantly related to the severity of the initial injury based on the AIS and the duration of the injury to surgery. They also showed that ASIA motor score (AMS) was associated with improved neurological outcomes while having prior underlying diseases reduced the chance of improved neurologic and functional outcomes. We could not estimate AMS in our study. Moreover, considering that most of our patients were <40 years old, the prevalence of underlying diseases in those patients is very low, and due to the small sample size in the subgroup of underlying diseases, we could not estimate its effect. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Ma et al. [22] reported that serial treatment of patients with TSCI with immediate decompression in the first hours after the injury (first 8 hours) can be significantly associated with neurological improvement. Evaniew et al. [16] evaluated 85 patients with TSCI and showed that older age, female sex, and delay in treatment were significantly associated with decreased neurological recovery, which is consistent with our results. Kao et al. [23] showed that obesity was negatively correlated with motor functional independence measure (mFIM) improvement. They showed that neurological improvement was lower in patients with a higher BMI than in those with a BMI, which was consistent with the results of our study.

The difference in rehabilitation recovery can be explained by the difference in characteristics and treatment participation between patients with inappropriate weight and those with normal weight. Tian et al. [24] showedthat participation in rehabilitation treatments was lower in patients with high body weight (BMI) than in patients with normal weight.

Facchinello et al. [20] showed that injury severity score, age, nerve level, and preoperative delay were predictors of neurological outcomes, which confirmed the results of our study. Contrary to our results, Furlan et al. [25] did not report a significant relationship between age and neurological recovery. This difference can be explained by the differences in the sample size and characteristics of the patients examined in the two studies.

Consistent with the results of our study, Heller et al. [18] showed that treating patients with TSCI in the first hours and days after injury was significantly associated with improved functional and neurological outcomes. They also showed that the improvement in the results was significantly related to the age of the patients, and the improvement was significantly higher in younger patients. This mechanism may be due to the increased inflammation in the early stages of ASI. They reported that an increase in the intermediate CD14-/CD16+/IL10+/CXCR4int monocyte subpopulation significantly enhanced the immune response in the early hours and days after injury. They reported that increased initial concentrations of CD14-/CD16+/IL10+/CXCR4int monocytes were associated with a higher probability of CNS regeneration and improved neurological recovery.

Conclusion

Our study showed that neurological recovery was higher in men than in women. Neurological recovery was lower in patients older than 30 years with a non-normal body mass profile (overweight or obese). Treatment in the early days and hours was associated with improved neurological recovery, while the severity of the initial injury was significantly associated with decreased neurological recovery.

Limitations

Our study had strengths and weaknesses. The most crucial weakness of this study was the short follow-up period of the patients and the small sample size of the subgroup with no recovery. We assessed neurologic outcomes 12 months after treatment, and the results may differ in longer-term follow-ups with larger sample sizes. In addition, due to the study design, we could not estimate a number of essential indicators, such as AMS, which may affect the study’s results. The design of prospective studies with a more extended follow-up period and a larger sample size can help make a more accurate estimate. The vital strength of this study was that it investigated the predictors of neurological recovery in a suitable sample size of TSCI patients in a multi-centered manner in the Iranian population.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran (Code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1401.505).

Funding

This study was taken from the orthopaedic surgery residency thesis of Mansour Paryab, approved by the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Hasan Ghandhari and Omid Momen; Methodology: Omid Momen; Investigation and data collection: Mansour Paryab; Data analysis: Mansour Paryab and Mahsa Arab; Writing: Habib Gorgani Firouzjah, and Afshin Sahebjamei.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- GBD 2016 Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019; 18(1):56-87. [DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30415-0] [PMID]

- Badhiwala JH, Wilson JR, Fehlings MG. Global burden of traumatic brain and spinal cord injury. Lancet Neurol. 2019; 18(1):24-5. [DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30444-7] [PMID]

- Barbiellini Amidei C, Salmaso L, Bellio S, Saia M. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury: A large population-based study. Spinal Cord. 2022; 60(9):812-9. [DOI:10.1038/s41393-022-00795-w] [PMID] [PMCID]

- van der Vlegel M, Haagsma JA, Havermans RJM, de Munter L, de Jongh MAC, Polinder S. Long-term medical and productivity costs of severe trauma: Results from a prospective cohort study. Plos One. 2021; 16(6):e0252673. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0252673] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ding W, Hu S, Wang P, Kang H, Peng R, Dong Y, et al. Spinal cord injury: The global incidence, prevalence, and disability from the global burden of disease study 2019. Spine. 2022; 47(21):1532-40. [DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000004417] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Golestani A, Shobeiri P, Sadeghi-Naini M, Jazayeri SB, Maroufi SF, Ghodsi Z, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in developing countries from 2009 to 2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2022; 56(4):219-39. [DOI:10.1159/000524867] [PMID]

- Chen C, Qiao X, Liu W, Fekete C, Reinhardt JD. Epidemiology of spinal cord injury in China: A systematic review of the chinese and english literature. Spinal Cord. 2022; 60(12):1050-61. [DOI:10.1038/s41393-022-00826-6] [PMID]

- Patek M, Stewart M. Spinal cord injury. Anaesth Intens Care Med. 2023; 24(7):406-11. [DOI:10.1016/j.mpaic.2023.04.006]

- Shiferaw WS, Akalu TY, Mulugeta H, Aynalem YA. The global burden of pressure ulcers among patients with spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020; 21(1):334. [DOI:10.1186/s12891-020-03369-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fouad K, Popovich PG, Kopp MA, Schwab JM. The neuroanatomical-functional paradox in spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021; 17(1):53-62. [DOI:10.1038/s41582-020-00436-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kirshblum S, Snider B, Eren F, Guest J. Characterizing natural recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2021; 38(9):1267-84. [DOI:10.1089/neu.2020.7473] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Li Y, Ritzel RM, Khan N, Cao T, He J, Lei Z, et al. Delayed microglial depletion after spinal cord injury reduces chronic inflammation and neurodegeneration in the brain and improves neurological recovery in male mice. Theranostics. 2020; 10(25):11376-403. [DOI:10.7150/thno.49199] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Xu BP, Yao M, Li ZJ, Tian ZR, Ye J, Wang YJ, et al. Neurological recovery and antioxidant effects of resveratrol in rats with spinal cord injury: A meta-analysis. Neural Regen Res. 2020; 15(3):482-90. [DOI:10.4103/1673-5374.266064] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bozzo A, Marcoux J, Radhakrishna M, Pelletier J, Goulet B. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the management of acute spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011; 28(8):1401-11. [DOI:10.1089/neu.2009.1236] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Richard-Denis A, Chatta R, Thompson C, Mac-Thiong JM. Patterns and predictors of functional recovery from the subacute to the chronic phase following a traumatic spinal cord injury: A prospective study. Spinal Cord. 2020; 58(1):43-52. [DOI:10.1038/s41393-019-0341-x] [PMID]

- Evaniew N, Sharifi B, Waheed Z, Fallah N, Ailon T, Dea N, et al. The influence of neurological examination timing within hours after acute traumatic spinal cord injuries: An observational study. Spinal Cord. 2020; 58(2):247-54. [DOI:10.1038/s41393-020-0413-y] [PMID]

- Roberts TT, Leonard GR, Cepela DJ. Classifications in brief: American spinal injury association (ASIA) impairment scale. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017; 475(5):1499-504. [DOI:10.1007/s11999-016-5133-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Heller RA, Seelig J, Crowell HL, Pilz M, Haubruck P, Sun Q, et al. Predicting neurological recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury by time-resolved analysis of monocyte subsets. Brain. 2021; 144(10):3159-74. [DOI:10.1093/brain/awab203] [PMID]

- Mora-Boga R, Vázquez-Muíños O, Pértega-Díaz S, Salvador-de la Barrera S, Ferreiro-Velasco ME, Rodríguez-Sotillo A, et al. Neurological recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury: Prognostic value of magnetic resonance. Spinal Cord. 2022; 60(6):533-9. [DOI:10.1038/s41393-022-00759-0] [PMID]

- Facchinello Y, Beauséjour M, Richard-Denis A, Thompson C, Mac-Thiong JM. Use of regression tree analysis for predicting the functional outcome after traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2021; 38(9):1285-91. [DOI:10.1089/neu.2017.5321] [PMID]

- Wichmann TO, Jensen MH, Kasch H, Rasmussen MM. Early clinical predictors of functional recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury: A population-based study of 143 patients. Acta Neurochir. 2021; 163(8):2289-96. [DOI:10.1007/s00701-020-04701-2] [PMID]

- Ma Y, Zhu Y, Zhang B, Wu Y, Liu X, Zhu Q. The impact of urgent (<8 hours) decompression on neurologic recovery in traumatic spinal cord injury: A meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2020; 140:e185-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.230] [PMID]

- Kao YH, Chen Y, Deutsch A, Wen H, Tseng TS. Rehabilitation length of stay, body mass index, and functional improvement among adults with traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022; 103(4):657-64. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2021.09.017] [PMID]

- Tian W, Hsieh CH, DeJong G, Backus D, Groah S, Ballard PH. Role of body weight in therapy participation and rehabilitation outcomes among individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013; 94(4 Suppl):S125-36. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2012.10.039] [PMID]

- Furlan JC. Effects of age on survival and neurological recovery of individuals following acute traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2022; 60(1):81-9. [DOI:10.1038/s41393-021-00719-0] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research Article |

Subject:

Spine surgery

Received: 2022/11/4 | Accepted: 2022/12/9 | Published: 2023/05/1

Received: 2022/11/4 | Accepted: 2022/12/9 | Published: 2023/05/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |